December 14, 2019–FEBRUARY 13, 2020

ARABESQUE IN MUSIC

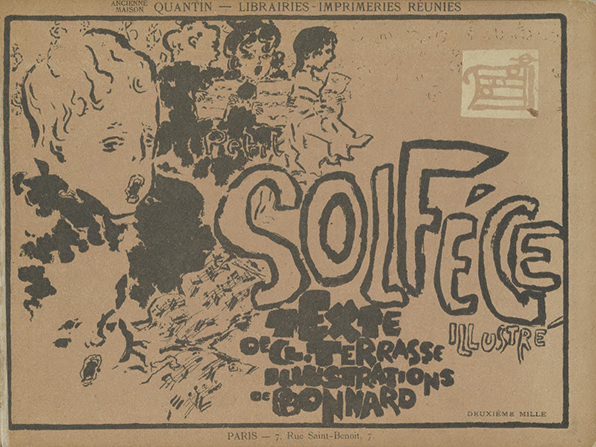

Pierre Bonnard (French, 1867–1947), Petit solfège illustré (Music Theory Illustrated), 1893. Photorelief prints in bound album, 8 3/8 × 11 1/4 × 1/4 in. Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Purchase, The Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions, 2007.106

In music, the term “arabesque” refers to a highly ornamental melody whose free unfolding expresses a slowing of time within the composition. Unlike the straight line, which is the most direct path from A to B, the curving movement of the arabesque creates an effect of circular phrases that conjure perpetual melodies.

The arabesque in music is often tied to visual ornamentation, just as visual ornament has been credited with musical qualities. British art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) equated the process of ornamentation in visual art with the composition of an abstract musical work. French artist Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), in his illustrations for Le petit solfège illustré, a music theory primer, conceived of sounds emerging from the score and instruments as floating ornaments, both figurative and abstract. The song of the music reverberates across the page, tangling the musicians’ hair in dancing arabesques. Claude Debussy (1862–1918), the nineteenth-century composer most associated with the arabesque, first mentions the term in describing the music of the Renaissance composer Orlando di Lasso (Flemish, 1532–1594), likening his melodies to the illuminated decorations of ancient missals.

Debussy’s best-known musical arabesque is his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894). The musical score was inspired by French Symbolist writer Stéphane Mallarmé’s L’après-midi d’un faune (1876), an eclogue (pastoral poetic dialogue) that centers on the sensual, dreamlike monologue of a faun as he longs for nearby nymphs. The decorative melody at the beginning of the piece evokes the poem’s imaginary music of the faun playing his flute but also the sonority of Mallarmé’s text, linking poetic and musical arabesques. Debussy’s melody is sinuous, fluid, and hazy, mirroring and pulling the listener into the faun’s yearnings and the mysterious dream-state of the poem. As an irregularly curving line, the melody suggests both dynamic energy and temporal suspense or stasis. Debussy’s arabesque functions on many levels, uniting in a single ornamental melody the timelessness of Mallarmé’s poem, the emotive qualities of frustration and yearning, and the imaginative song of the faun’s dream.

Featuring an essay by Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, Arabesquetraces the role of this curvilinear decorative motif through a variety of styles and media in European art. An elegant companion to the exhibition, this sixty-four-page softcover publication includes fifty-seven color illustrations highlighting objects from the show and their influences.